How "The End of Sanctions" Is Changing Corporate Discovery

Spoliation sanctions have become increasingly rare in recent years. And when it comes to the most severe sanctions, these are increasingly off the table.

For an industry where the threat of eDiscovery disasters has long played an outsized role in influencing behavior (consider the impact of the Zubulake decisions, for example, or the disciplinary actions that followed botched discovery in Qualcomm v. Broadcom), how are legal professionals reacting to “the end of sanctions?”

For innovative, data-rich corporate legal departments, "the end of sanctions" means rethinking their entire approach to preservation and discovery, redesigning workflows in light of the new sanctions regime, and building out defensible, and documented, disposition policies.

Rule 37(e) and “The End of Sanctions”

First, let’s start with the start—of the new sanctions regime, at least. On December 1st, 2015, new amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure went into effect. Among the most important changes was the wholesale reworking of Rule 37(e), governing sanctions for the spoliation of electronically stored information.

Following that change, exhaustive new research by Logikcull shows, there has been a significant decline in spoliation sanctions issued in federal civil litigation.

That amendment was made, in the words of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, to avoid the expenditure of “excessive effort and money on preservation in order to avoid the risk of severe sanctions” that litigants faced prior to the new rule.

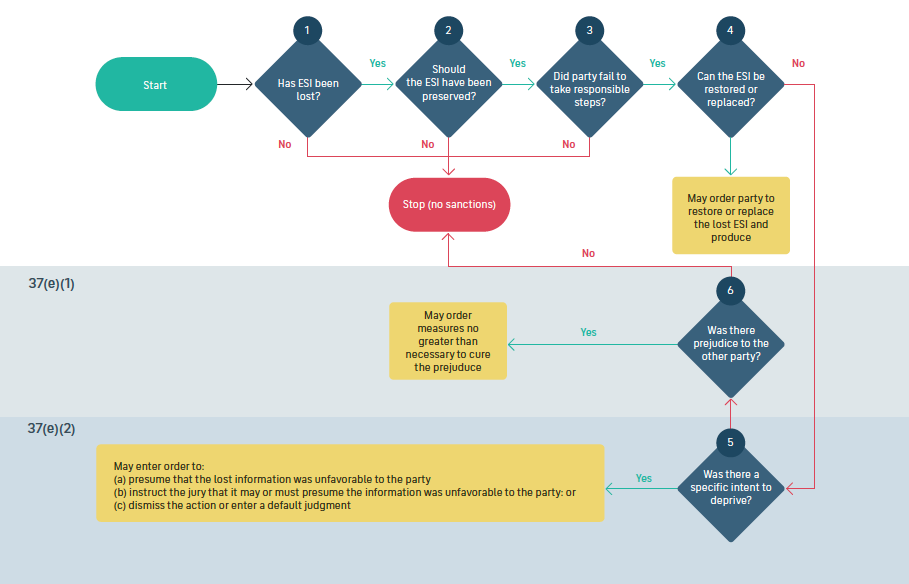

To do so, Rule 37(e) created a dual-pronged approach to sanctions, restricting courts to solely curative measures in most cases and reserving the most severe sanctions to cases where there has been a showing that a party spoliated potential evidence with “the intent to deprive another party of the information’s use in the litigation.”

That means that today, sanctions motions must overcome a host of barriers in order to be granted, as the workflow below shows:

A massive reduction in the number of spoliation sanctions issued by federal courts has followed, as a survey of more than 300 cases by Logikcull reveals. That research shows that, in the years following the 2015 amendments:

- Spoliation sanctions have declined by 35%

- The severest sanctions are denied in 4 out of 5 cases

- Only one in every 8,000 federal civil court cases involves motions for spoliation sanctions

Gone are the blockbuster, multi-million dollar sanctions for errors that were arguably “mere negligence”—the kind of sanctions that once terrified the bar. Motions for sanctions are down by more than one third, and when litigants do ask for severe sanctions, courts seem to be very comfortable saying “no,” fully granting only 18 percent of such motions in 2018.

As a result, those amendments are impacting everything from information governance to data preservation and litigation generally. In a recent webinar on “the end of sanctions,” the vast majority of participants said they had either already changed their approach to discovery in light of the 2015 amendments (29 percent) or were planning to change (44 percent).

Changing Approaches to Data Preservation

By re-working spoliation sanctions, the new Rule 37(e) has reduced the likelihood that legal teams will be punished for mistakes they commit during discovery—a shift that has eased the pressure on in-house legal teams and allowed companies to re-focus on what matters: preserving relevant data efficiently and defensibly.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that the legal questions around eDiscovery are completely solved. Corporate litigants are still struggling with how to respond to the Rule 37(e) amendments and dealing with issues such as:

- How to reconcile seemingly contradictory jurisprudence in the post-amendment discovery landscape

- How to develop and implement defensible deletion procedures

- How to involve outside counsel in discovery while also reducing legal spend

Which is why we recently caught up with Craig Ball, a trial lawyer, computer forensic examiner, law professor and noted authority on electronic evidence, and Mira Edelman, who has decades of in-house eDiscovery experience at some of the world’s largest companies, for a recent webinar to discuss, among other things, how the Rule 37(e) amendments are changing—or should be changing—the way lawyers look at data preservation.

Rethinking Data Preservation: From Risk Aversion to Risk Awareness

One of the biggest impacts of 37(e)’s new “intent” standard is that it has triggered a marked shift in in-house preservation practices, allowing corporate legal departments to take a whole new approach to their discovery process. As Mira Edelman, who was Senior Counsel and Discovery Director at Google when the amendments went into effect, explains:

At the time that these rules came out, I was in-house at Google. They gave in-house counsel legal authority to give us the ability to do what we'd wanted to do all along: to reduce what we were preserving. These rules allowed us to look at what was reasonable and proportional in conjunction with Rule 26. It allowed us to instruct our outside counsel to not be so conservative. It allowed us to influence them so that they would not have any issues about certifying discovery based on the “bad actor” type of analysis.

It allowed me to put forward a philosophy that was more about risk awareness instead of being risk-averse.

How is that shift put into practice?

For Edelman, it started with rethinking Google’s preservation and discovery workflow.

That included thinking more broadly about company information, she explains, “beyond just the context of litigation.”

How would, for example, overly broad preservation impact data security efforts? How would data privacy concerns be affected by information governance decisions? How might preservation be reworked to avoid keeping data under a permanent legal hold?

Workflows were then reworked in light of the new sanctions regime.

That approach was not unique to Google. “Subsequently, when I was at Facebook,” recounts Edelman, who served as Director of eDiscovery and Information Governance at the social media giant after Google, “I was able to leverage these smart preservation strategies by aligning with other business leaders who were addressing data privacy and the emergence of GDPR.”

It was an approach that wouldn’t have been easy without the 2015 revisions. “I think this was really what we needed and believed all along should be the appropriate approach for preservation,” Edelman says. “The rules amendments gave in-house counsel teeth to take that approach and direct our outside counsel to follow those structures.”

The emergence of better tools and growing technological competency among the bar have also helped spur these changes, Edelman explains:

I think that, in addition to relieving some of the pressure of the new rule, our technology has improved. We know how to better preserve, collect, search, and review information. I think lawyers have become a little more sophisticated. Companies are engaging specialists to come and help them do their work properly.

That combination of new rule language and growing body of sophistication in the legal profession to handle eDiscovery can open up opportunities for companies that maybe haven't been doing this before in the same way.

Since the most severe sanctions hinge on the showing that data was destroyed with “an intent to deprive,” showing the reasoning behind data disposition becomes increasingly important. At Google and Facebook, Edelman says, “We focused on creating a sensible workflow, documenting our decisions on what we were preserving, and what we determined not to preserve.”

Others can follow suit. “Create documentation that supports why that data may have been deleted,” Edelman advises, “so there is a narrative that can be used as evidence that shows that the deletion was not done to deprive the other party of evidence.”

What the End of Sanctions Means for In-House Legal Professionals

By reducing the amount of data preserved for litigation, and creating a documented, defensible workflow around those decisions, Edelman was able to:

- Rework preservation policies to take account of data preservation’s implications beyond just litigation

- Pursue competing imperatives, such as data security and privacy

- Reduce the cost and risk associated with over-preserving corporate data

- Shift from a purely “risk averse” approach to data preservation and litigation to one that is “risk aware”

Of course, data-rich corporate parties aren’t the only ones adjusting their strategies in light of the “derisking” of discovery. Stay tuned for an upcoming post featuring Craig Ball’s suggestions on how movants for spoliation sanctions can take advantage of the new regime themselves—and in potentially surprising ways.

Learning With Logikcull

Browse our latest resources for innovative legal teams like yours

Stay in the know

Get the latest news, expert guidance, and interviews delivered straight to your inbox so you're always one step ahead.

Get the latest updates

Want to see it work?

Request a demo today.

Managing FOIA requests with limited staff, strict deadlines, and pressure to protect sensitive data?

Logikcull is built for this.