Judge David Campbell: eDiscovery Software rarely proposed, rarely used

This is the second part of Logikcull's interview with US District Court Judge David Campbell, the former chair of the advisory committee responsible for drafting newly promulgated amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In part one, Judge Campbell addressed the prospective impact of the rule changes, and what their emphasis on proportionality and cooperation may mean in practice. He also outlined the evolution of the federal spoliation sanction rule, 37(e), which has been the focus of much debate and handwringing.

Here he discusses what other measures must accompany the rule changes to bring a substantive reduction in litigation costs, speed case resolutions, and reopen the federal court system to those it has priced out. We also ask him to share his experience with predictive coding and how it is -- or is not -- being used in his courtroom.

Logikcull: In the commentary to Rule 37, the committee noted that “The court should be sensitive to the party’s sophistication with regard to litigation in evaluating preservation efforts; some litigants, particularly individual litigants, may be less familiar with preservation obligations than others who have considerable experience in litigation.” Has anybody challenged that language as potentially giving a free-pass to litigants who are “willfully ignorant” — or maybe just lazy — when it comes to their preservation obligations?

Hon. David Campbell: I have not heard those challenges. It may well be that some folks have that concern. I will tell you, from my perspective, a very important background for this rule change is that the reality is that ESI in now in the possession of everybody. The personal injury plaintiff who walks into the lawyer’s office on crutches after the car accident has ESI that’s relevant to the injury, whether it’s their Facebook page, or the text they sent to their girlfriend after the accident, or communications with their doctors, or emails they might have sent. And that’s a very different world than we lived in 20 years ago. The reason for the comment you just read from the committee note is that if that person turns out to have not stopped Facebook’s deletion of posts — and I don’t know how Facebook deletes posts, but just use that as a hypothetical — a court can take into account their lack of sophistication in deciding later what Rule 37(e) measures should be imposed.

And I think that’s right. I don’t think we should hold them to the same standard as an entity that has an IT department. A number of the most prominent cases on the loss of ESI — I believe this is correct — deal with the plaintiff’s loss of ESI.

We had an expert tell us in one of these (rules committee) hearings that by 2018 — maybe he said 2020 — there will be 26 billion devices on the internet, which is, you know, four for every person on Earth. And the truth is, I believe, five years from now, 10 years from now, the amount of information that each person has in the cloud will be equivalent to the kinds of records that use to be found in the filing cabinets of entire businesses. So ESI, in my view, isn’t just a problem for the big entities. It’s a litigation issue for everyone, and this rule (Rule 37(e)) tries to take that into account.

"FIVE YEARS FROM NOW, THE AMOUNT OF INFORMATION THAT EACH PERSON HAS IN THE CLOUD WILL BE EQUIVALENT TO THE KINDS OF RECORDS THAT USE TO BE FOUND IN THE FILING CABINETS OF ENTIRE BUSINESSES. SO ESI, IN MY VIEW, ISN'T JUST A PROBLEM FOR THE BIG ENTITIES. IT'S AN ISSUE FOR EVERYONE."

Logikcull: Well, to that point, data growth is accelerating at an incredible rate. Is there any fear that whatever cost-lowering impact these changes will ultimately have will be negated by the fact that, not only is there going to be exponentially more data, but also that the technology available to handle that data does not appear to be getting much cheaper? Do you have that concern? I imagine you do.

Judge Campbell: I do. I think any judge or any lawyer involved in litigation should. We are hoping that these rule changes help through Rule 37(e) in bringing some level of uniformity of how you deal with the loss of information. We hope Rule 37(e) will reduce the amount of side litigation that occurs over loss of ESI and sanctions. The proportionality change and the case management changes, as well, are intended to get judges involved earlier in cases and work with the parties in figuring out how we get cases resolved efficiently given many factors, one of which is ESI which has to be dealt with in the case.

I don’t pretend to believe we’ve solved the problem. I think you’re right - we don’t really foresee the extent of the problem and it’s something that the courts are going to have to adapt to. But our intent is to at least make some progress on dealing with ESI through these amendments.

"I DON'T PRETEND TO BELIEVE WE'VE SOLVED THE PROBLEM. WE DON'T REALLY FORESEE THE EXTENT OF THE PROBLEM."

Logikcull: Judge, what’s your sense of how well technology — and I’m now talking about the legal provider side, or e-discovery vendor side — has developed and been adopted by practitioners to counter these rising data volumes? I’m particularly interested in knowing your thoughts on, if you’ve even seen it, the utility of predictive coding… The field has put a ton of faith into that process and others, and into technology in general — and it seems to me, anyway, that the results have been somewhat underwhelming. Do you have an opinion on that?

Campbell: I’ve got some thoughts. I don’t know if they’re mature enough to call them an opinion [laughing]… I think it’s a reality that, going forward, we’re going to have to find technological solutions to this growth of ESI. The reality is that the old model of having lawyers or paralegals review every document that’s produced is not going to work. It just can’t work in a world where you’re dealing with millions of documents. We either incur enormous expenses continuing that model; or we surrender and produce everything — which I don’t think lawyers are going to do; or we need to find a technological way to winnow down the ESI to a manageable size.

So my view is, whether it can accurately be said that, today, technology is solving the problem, ultimately it’s going to have to solve the problem, because I don’t think the court system and lawyers are going to be able to continue dealing with it the way we dealt with paper evidence.

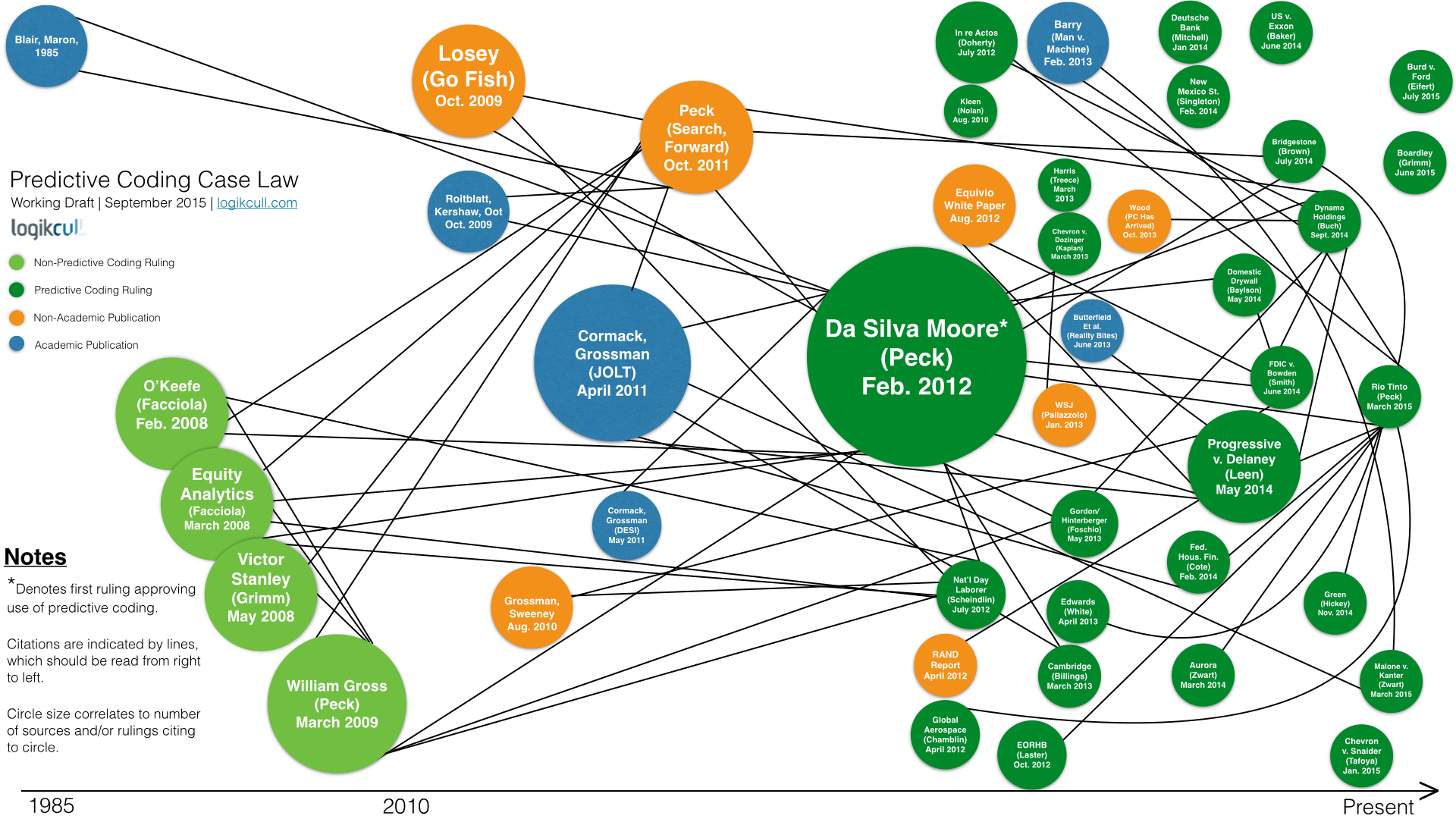

I will also say that I’m finding in my cases that predictive coding or technology-assisted review is rarely proposed by the parties and rarely used. I think that will change over time. I’ve seen more of it over the last few years. But it is still used in a very small percentage of the cases. And I am surprised at the number of big document cases where the parties do not use it, even when I suggest it. They instead prefer keyword searches.

I think part of that is the need to educate the bar through sophisticated litigators as to what the technology can do, and it is my hope that the predictions will prove true that it really can do this more quickly and more accurately than people.

But I’m not seeing it used widely in my cases, and, you know, Phoenix is the fourth or fifth biggest city in the United States. So I think we have our share of complex cases, and yet it is still a rare commodity in my cases.

"WHETHER IT CAN ACCURATELY BE SAID THAT, TODAY, TECHNOLOGY IS SOLVING THE PROBLEM, ULTIMATELY IT’S GOING TO HAVE TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM, BECAUSE I DON’T THINK THE COURT SYSTEM AND LAWYERS ARE GOING TO BE ABLE TO CONTINUE DEALING WITH IT THE WAY WE DEALT WITH PAPER EVIDENCE."

Logikcull: You mentioned the emphasis in the rule changes on making judges more proactive case managers. Judge [Paul] Grimm [of the federal District Court in Maryland], among others, has been pretty vocal about the idea that judges do not traditionally view themselves as case managers, but as dispute resolutionists. What’s your assessment of how well the judiciary will be able to take a more proactive role in facilitating some of these e-discovery issues?

Campbell: I have no illusion that simply re-writing the rules is going to transform judges from passive to active case managers. It clearly won’t. And as you know, the idea of active case management has been in the Federal Rules since 1983, when Rule 16 was revised to create an active role for judges. So we have been of the view that these rule changes need to be accompanied by a very significant education effort to encourage judges, in particular, to be more active case managers. Many are. But Judge Grimm is right that many still are not.

There are a number of steps we’ve taken. Members of the committee have written articles. We’ve created videos that are now on the Federal Judicial Center website that have been sent to every federal judge in the country explaining the rule changes. The committee has written letters to every chief district judge and every chief circuit judge in the country asking that they include the new rule amendments in district and circuit conferences next year to educate judges and lawyers about them. We’ve compiled materials that are available for judges on the FJC website — articles, PowerPoints and other things. And the Federal Judicial Center, which is the entity that trains judges, is intending to do more active training of judges. We’re hoping that that push, along with the rule changes, will bring about a behavior change on the part of us judges. Whether or not it works, we’ll have to see over time. But I’m hoping, at least with many judges, it will produce more active case management.

Logikcull: To stay on this theme of education, but now turning to educating the bar and practitioners… I get the sense, just as an outside observer, that there is an education gap. You have some small percentage of highly knowledgeable people who are technically competent who typically, though certainly not always, come from the largest law firms and largest corporations. And then you have some large remnant that tends to not understand this stuff at all. You’re at the federal court level. Is that what you’re seeing? Or are you seeing a general rising of education?

Campbell: Well I certainly see lawyers who understand the rules and are dealing with ESI better than others do. But I don’t think I would say that you find all of the best prepared lawyers in the large law firms or large corporations. I see many lawyers who are sole practitioners or who are in small firms or government attorneys who are right on top of ESI and the rules.

But there’s no doubt that many are not. I think that is changing. I alluded to it a moment ago, I’m seeing more and more — although it’s still a fairly small percentage — thinking about things like technology-assisted review. And I’m definitely seeing more who are dealing with ESI up front and talking about it at the Rule 26(f) conference. I’m hoping that the publicity that occurs in connection with these rules amendments — and there is a fair amount of publicity going on through various bar groups — will educate lawyers about these ESI issues in a way that they haven’t been before. As I said earlier, we have to deal with ESI in the federal courts. I think everybody involved is becoming more and more aware of it — and we’ll see lawyers become more sophisticated over time.

"I'M SEEING MORE AND MORE (LAWYERS) -- ALTHOUGH IT'S STILL A FAIRLY SMALL PERCENTAGE -- THINKING ABOUT THINGS LIKE TECHNOLOGY-ASSISTED REVIEW."

Logikcull: Some practitioners see the expense associated with e-discovery as an access to justice problem. Judge John Facciola has gone so far as to say that e-discovery is contributing to making the federal court system a “playground for the rich." Is that a sentiment that you share?

Campbell: I don’t think I would call it a "playground for the rich," but I absolutely agree that too many people cannot afford to litigate in federal court. I do think the cost of federal litigation makes it unavailable to the average citizen. And I see many of them who are representing themselves struggling to handle a case because they can’t get a lawyer to take it because it doesn’t have enough money at stake. I think that’s a problem.

"I DO THINK THE COST OF FEDERAL LITIGATION MAKES IT UNAVAILABLE TO THE AVERAGE CITIZEN. AND I SEE MANY OF THEM WHO ARE REPRESENTING THEMSELVES STRUGGLING TO HANDLE A CASE BECAUSE THEY CAN'T GET A LAWYER TO TAKE IT BECAUSE IT DOESN'T HAVE ENOUGH MONEY AT STAKE."

That’s one of the problems we talked about at the 2010 conference that I mentioned. Part of our intent in putting the proportionality idea into the new rules and trying to get judges to actively manage cases more efficiently from the beginning, and we hope cutting down the side litigation over the loss of ESI, is to reign in the cost of discovery. There are other things that the Civil Rules Committee and other Judicial Conference committees are looking at to try to make civil litigation less expensive.

But in my view, it absolutely is a problem, and one that we need to work hard as a federal judiciary to solve.

As told to Robert Hilson, a director at Logikcull. He can be reached at robert.hilson@logikcull.com.

Learning With Logikcull

Browse our latest resources for innovative legal teams like yours

Stay in the know

Get the latest news, expert guidance, and interviews delivered straight to your inbox so you're always one step ahead.

Get the latest updates

Want to see it work?

Request a demo today.

Managing FOIA requests with limited staff, strict deadlines, and pressure to protect sensitive data?

Logikcull is built for this.